Hal Willner, one of modern music’s greatest producers and creative auteurs, died two days ago in New York. Reports have stated that “no cause of death has been confirmed, but he was said to be experiencing symptoms consistent with the coronavirus”. He was 64.

Willner was a free-spirited producer who worked in music recording, television, film, and live performance, and who had a compelling and catholic love of music, as well as for comic books and comedy – anything, really, that was surreal, screwy or avant-garde.

I interviewed Willner in New York in April 2017 for my biography of Bill Frisell. Bill and Hal go back a long way, right back to 1980, to shortly after Frisell had moved to New York, when Willner was putting together a celebration of the music of Fellini film composer Nino Rota.

“I needed a solo guitarist, because of budget, and I was asking around, and [drummer] D Sharpe told me about Bill,” Willner said. “Bill sent me a cassette – it was in this torn envelope I remember – and oh God, I actually had him sort of audition for me. He was almost clinically shy back then. He really didn’t talk. Hardly ever. Carole [Bill’s wife] was sort of his… spokesman.”

The result was “Juliet of the Spirits”, the remarkable unaccompanied Frisell track on the 1981 album Amarcord Nino Rota; it was Bill’s first American session under his own name, and one of his big New York breaks.

Numerous Willner and Frisell collaborations followed. There were further “various artist concept records” (Willner disliked the term “tribute album”) – defiantly cross-genre projects that took inspiration from the music of, among others, Charles Mingus and vintage Disney films.

Frisell also appeared on Willner-produced albums for Marianne Faithfull, Allen Ginsberg, William Burroughs, David Sanborn, Lucinda Williams, Laurie Anderson, and Gavin Friday, and on compilations of pirate ballads, sea songs and shanties.

There were live concerts exploring the work of Randy Newman, Harry Smith, Daniel Lanois, TS Eliot, and Hunter S Thompson; the late-night jazz-and-beyond TV programme Sunday Night (later Night Music); and film scores – Frisell worked with Willner on Wim Wenders’s The Million Dollar Hotel and Gus Van Sant’s Finding Forrester.

In 2004, Willner produced Bill Frisell’s album Unspeakable, which won the first and only Grammy for both musician and producer. “There are these few people in my life who create an atmosphere that allows me to do interesting things,” Frisell has said. “Hal is one of those people. He creates these opportunities and invites me into them. He doesn’t tell me what to do, so I have to figure it out.”

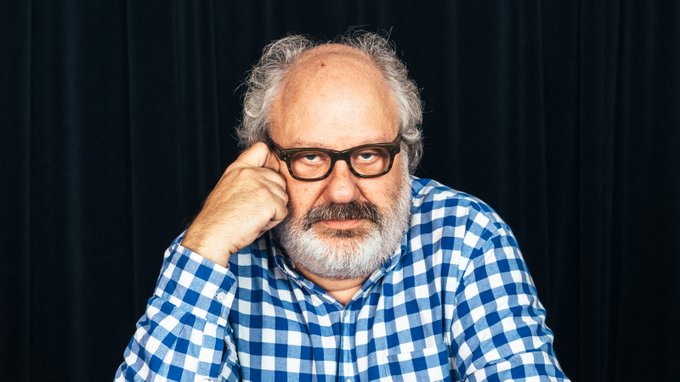

Hal Willner, Bill Frisell and Eyvind Kang at The Stone, New York, in 2014 (photograph by Marc Urselli)

Hal and I met at Willner’s tiny studio in the Hell’s Kitchen district of Manhattan; as I arrived he was playing a track from the vinyl record Fanti Guitar in West Africa 1928, Vol 1 by the Kumasi Trio. Made in London, these are some of the first ever recordings of traditional African music played on western instruments. It seemed very Hal.

His workspace resembled a bright and precocious child’s bedroom. Around him were shelves and boxes overflowing with his myriad obsessions and diversions: records, CDs, posters, figurines, a Popeye doll, busts of Laurel and Hardy, a David Bowie puppet, photos of Lenny Bruce, a DVD of the British TV comedy series Dad’s Army, a ghoulish open-mouthed mask of Donald Trump.

Willner may have spoken in his characteristically gruff and sandpapery drawl, which was sometimes, for me at least, a little hard to understand, but he was unequivocally an original thinker, inquisitive polymath, gentle provocateur – and a gift of an interviewee.

My conversation with Willner is the first of the book’s “segues” – listening sessions in which I play tracks from various Frisell albums to well-known figures in music and the arts, including Paul Simon, Gus Van Sant, and Justin Vernon of Bon Iver. I played Hal some selections from Bill’s 1988 album Lookout For Hope. Here are two extracts from the interview…

PW: I’m going to start by playing you Bill’s three-minute version of [Thelonious Monk’s] “Hackensack”.

HW: [As the track ends, laughing] Yep, one note and you know who it is. That… is… wild. Insane. [Laughs again]. I don’t know any one other guitarist who can do that. I just think it comes from here [points to his heart].

You know, some people have to practise eight hours a day, and it’s said some don’t and it comes a lot easier, but I think for most musicians becoming a virtuoso on an instrument is an achievable skill. But it’s what you do with it after that. And Bill did as much as you possibly can do.

When I think of Bill, or hear him, like now, I don’t think of him as a guitarist, as ‘guitarist Bill Frisell’. Ever. It’s too limiting. Like [Marc] Ribot, he’s a master musician who just happens to play guitar. I don’t hear guitar with Bill; I hear this other thing.

And what is that?

It’s the spiritual thing that I sometimes talk about. The second you hear that sound, he has you one hundred per cent. It’s like jumping into an ocean. As soon as you hear the first notes, you’re in that world; you’re in a different part of the forest, you know.

A highly individual and personal quality that takes you to another place?

Yes, that’s what you’re looking for, what makes him different to anything else. When I’m putting together any personnel, for an album or live show, I’m looking for that difference, and for differences between people. Like putting this real commercial guy next to this real avant-garde guy. Which was always an important element: a taste for the avant-garde. Some of us aren’t the ones who skipped the “Revolution 9” track [on The Beatles’ White Album].

* * *

Do you think Bill’s abilities as a composer and arranger have been overlooked?

That’s why I’ve created projects with Bill, such as The Kentucky Derby [Is Decadent and Depraved, based on Hunter S Thompson’s seminal gonzo article] and [Allen Ginsberg’s beat poem] Kaddish, in which I’ve asked him not to play. Don’t play. Just write, just conduct. And people questioned me about that, but God, he got so excited when I asked him and it brought out yet another side to Bill.

It was the same with Unspeakable; I thought, what haven’t we done? Bill’s been jazz and country and avant-garde and da-da-da-da – he’s done everything – and it didn’t even occur to me to repeat any of that. I thought, ‘Forget the outside world: what is the Bill Frisell album you’d want to hear next?’

So I thought, ‘What about funk?’ A lot of non-African Americans have an interesting take on funk; some of my favourite funk has been made by white guys, in fact. Including, now, Bill. Because he listens to everything and I knew he would play his own version of funk, take it in a different direction. And it was successful. It won a Grammy that year; Bill’s Grammy.

* * *